Sweeping mortgage boycott changes the face of dissent in China

It began with a 590-word letter penned by angry purchasers of the half-built Dynasty Mansion project, whose pleas for China Evergrande Group to complete homes they’d long been paying for had fallen on deaf ears. “All homebuyers with outstanding mortgage loans will stop paying,” unless construction resumes before Oct. 20, they threatened.

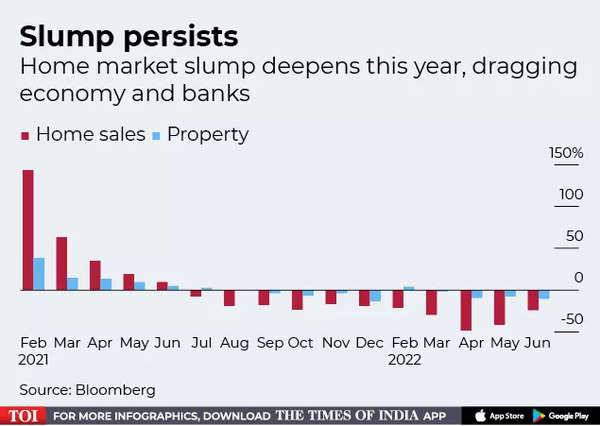

The ultimatum raced across social media platforms WeChat and Douyin, becoming a call to action for those caught out by China’s rapidly deflating property bubble. In days, the letter became a template for protests from Shanghai to Beijing, and Shenzhen to Zhengzhou, with homeowners cutting and pasting from it to draft their own boycott manifestos. Within four weeks, more than 320 projects in about 100 cities were facing similar protests, roiling markets and forcing authorities to corral banks and developers to defuse the unrest.

“We didn’t mean to make a scene deliberately, but we didn’t have a choice,” said one buyer at the 14-tower Evergrande project in the city of Jingdezhen, who asked not to be identified for security reasons. “All we want is the attention of the local government. We hope they bear the responsibility.”

The protesters have achieved much more. With social stability a must ahead of this year’s Communist Party Congress, their voices have reached the highest office. President Xi Jinping’s Politburo last week called on local officials to “ensure the completion” of housing projects, and state-owned banks are being strong-armed to finance the work.

Censors have simultaneously stepped in to quell dissent, scrubbing posts, silencing protesters and banning document-sharing links. Still, the breadth of the support, and the speed with which it spread, shows that the Chinese aren’t afraid to band together on a national scale, especially when their treasured homes are at stake. While real estate has been the most common cause of protests in recent years, a co-ordinated boycott of this scale has never happened before in China, said Christian Goebel, a University of Vienna professor who studies the topic.

“The security services must be very concerned about how quickly this movement spread, not just within cities but across the country,” China-watcher Bill Bishop noted in a recent newsletter. “Cross-geography organizing is the stuff of nightmares for the government.”

For the 100 or so buyers who signed that first letter, complete with red fingerprint stamps, it was a last resort after every other effort to get construction finished had failed. Though the protest exploded across social media with the letter posting on June 30, homeowner frustration had been brewing for months.

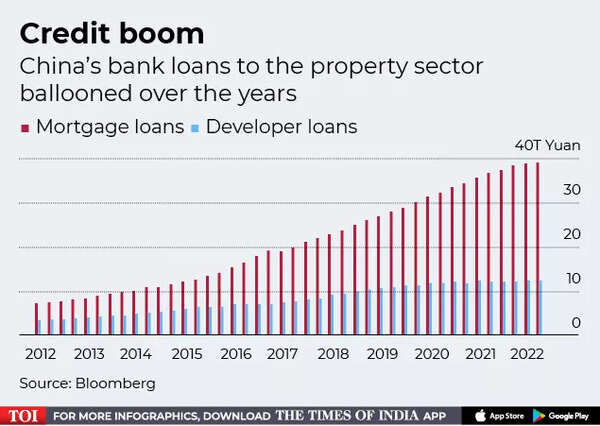

A crackdown on overleveraged property firms that started in 2020 sparked a liquidity crunch and kept developers like Evergrande out of credit markets, depriving them of cash to complete the apartments. Suddenly, construction that used to take 12 to 18 months was taking years, or was halted altogether. All the while, buyers had to keep paying their mortgages, a quirk of the Chinese market where payments start with a pre-sale deposit, long before work is complete.

Homeowners staring at unfinished gray concrete blocks, and watching developer after developer default on their debt, began to compare notes about what to do to salvage their investments.

Li was one of them. Checking on the construction site of his yet-to-be-built apartment in Wuhan had become a form of mental torture, he said. He made a 40% down payment on an Evergrande condo, eating up all his savings after several frugal years. Whenever he visited the complex of 39 skyscrapers he would see one or two workers, with only a few machines humming.

“I only hear the birds sing,” said Li, a 26-year-old tech worker who didn’t want his full name used for security reasons. “If I have to pay a mortgage for a home that’s never going to be finished, I feel my whole life would be ruined. Deep down, that makes me terrified.”

With frustration mounting, one homebuyer in Jingdezhen brought up the idea of a mortgage boycott in a WeChat group. The move wasn’t without risk, as any missed payments can ruin a credit score and make it harder to buy real estate down the line. Still, a few others echoed the idea after hearing of buyers doing the same at several Evergrande sites. Others turned to Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, where many disgruntled people had posted their own videos and photos.

Those voices languished though until the letter from Jingdezhen landed. After delivering it to authorities, the boycotters pasted the missive on Douyin. Homebuyers in dozens of projects followed suit each day, copying the letter and publishing similar pleas there and on the Twitter-like Weibo platform. Some posts attracted millions of “likes.” They uploaded videos of stalled construction sites, along with photos of notes detailing negotiations and their quarrels with local authorities. The demands also grew bolder, with buyers seeking home completion in a month.

The collective movement, both sudden and unprecedented, was dubbed “tingdai” in Chinese, a phrase taken from the first boycott letter that typically refers to banks halting home loans. “Duangong,” or halting mortgage payments, would have been more accurate, but “tingdai” continued to trend on social media, demonstrating the influence of that first letter.

A shared document managed by a lawyer using online platform Zhihu Inc. became the public battleground, tallying the extent of the protests as more home owners joined the fight. It was quickly picked up by research firms and global investment banks like Citigroup Inc. to assess the impact of the boycott. The lawyer confirmed he compiled the list, but wouldn’t comment further.

As the protests mushroomed—and even spread to construction suppliers—authorities took steps to stifle them. Document-sharing links such as kdocs and wolai were banned, as well as overseas platforms like Google Docs and Notion. Only a web page on the GitHub community remains accessible, in part because the platform is vital for many Chinese tech companies.

Posts listing all the delayed projects were deleted, as were numerous social media accounts of furious homebuyers. Some of them told Bloomberg News that they had been contacted by police. Meanwhile, the majority of buyers in the Evergrande project where it all started have “shut their mouths,” according to one person, who was also warned by police to stop posting on social media.

Evergrande, the property giant at the center of China’s real estate crisis, declined to comment on the boycotts.

With the online movement increasingly censored, some have turned to the old-school approach of street protests. On July 25, a loosely organized group of about 50 people went to the county government in Jingdezhen demanding action. Waving small national flags, they chanted “Restart Construction, Restart Mortgage Payment (早日复工,早日还贷).”

Even as the movement slows amid the social media crackdown—and homebuyers await concrete results—supporters can take solace knowing the revolt has sparked plenty of responses. In Jingdezhen, authorities have pledged to press Evergrande to restart construction, according to one of the protesters. The city government is asking four state-owned firms to tackle Evergrande projects, aiming to deliver them by the end of 2023, according to a July 8 update posted on the city’s website. Calls to Jingdezhen government and housing authorities went unanswered.

Nationally, there has even been some discussion of a mortgage holiday for buyers until construction is complete, Bloomberg News reported. The government is also pushing banks to lend to developers to get projects done, and may take over undeveloped land from distressed companies to pay for the work, according to people familiar with the matter. In addition, China plans to set up a central bank-backed fund to finance construction, people familiar said. The People’s Bank of China didn’t immediately respond to a fax seeking comment.

The boycott shows “something is really wrong with China’s real estate sector,” said Goebel in Vienna. “In terms of teaching a lesson, I think the government is more likely to target the companies than the homeowners.”

Still, it remains to be seen whether all the proposed money will be delivered and how soon the apartments will be finished. Homeowners like Peter, who bought a 2 million yuan ($296,000) condo in Zhengzhou last May after borrowing from his parents and saving for years, want it all to end.

“The developer has caused us tremendous harm and a lot of homeowners are depressed,” he said. “I just want to get my apartment.”